Charter Isomorphism, or the Charter Sector Trying to Un-sector Itself

On June 12, 2017, the Center for Education Reform (CER) announced that it published a “new book” (which I would call a report) entitled, “Charting A New Course: The Case for Freedom, Flexibility, and Opportunity Through Charter Schools”.

According to the CER press release, it seems there is a rift among charter school advocates. Here is how CER frames it:

The book compares the approaches of the two main groups in the charter-school world: those who want to empower bureaucrats and politicians, and those who want to empower parents.

In the intro of the 120-page book/report, CER founder and CEO, Jeanne Allen et al. term these two groups as “system-centered reformers” and “parent-centered reformers,” respectively:

System-centered reformers want to arrive at higher quality educational options by expertise-driven management. They believe that bureaucrats and politicians should have ample authority to decide what schools may open and what schools must close using standardized test-scores to make data-driven decisions.

Parent-centered reformers trust parents more than bureaucrats when it comes to determining school quality. They want to see a more open and dynamic system, where educational entrepreneurs are freer to open new schools and parents decide which schools should close and which should expand based on whether they want to send their children there.

Note that the tag, “parent-centered reformers,” still has parents in a secondary role to the edupreneurs, who open schools. But the parents would get to decide if the schools close or expand. Allen et al. want to shake off the test score criteria. Let the parents decide. How parents will manage to keep a school open or expand a school if the CEO squanders funds is unanswered. Furthermore, those with money and political pull will somehow be kept at bay so that the parents can run the charter show. Or at least some subset of parents can run it, somehow. And that without corporate charter advocate infiltration or corruption.

I’ll let it go for now.

Following its introduction, CER’s book/report has four sections. In the first section, Allen offers a “long essay” in which she focuses on the “isomorphic drift that’s made the charter sector come ever closer to mirroring traditional schools,” which is a terrible issue, I am sure, but the heavy, billionaire-philanthropic role in the charter sector isomorphism is certainly not familiar to traditional public education. Understatement alert: Traditional public education is not receiving excessive billionaire funding.

In this blog post, I focus on excerpts from two parts of the CER book/report: its introduction and Allen’s long essay.”

As one might expect, Allen is in the “parent-centered reformer” camp, which makes for some interesting reading for this traditional public school teacher who has heard and read ad nauseam how public education is *failing* (international and national test scores being the end-all evidence of this, of course) and how school choice will overcome such failure. (Again, the corporate reformers themselves have selected standardized test scores as the measure of failure; this, it by default the measure of school choice success. If the test scores are set aside, then the traditional public schools aren’t the failure that they must be in order for school choice to appear to be the shining solution.)

So, let’s consider some excerpts from CER’s book/report intro:

We are concerned about institutional isomorphism in the charter sector—the tendency of charter schools to look and act more and more like the traditional schools they were intended to substantively supplement.

Note the above term “supplement.” Note also that the term will be replaced with the “supplant” idea shortly. Continuing:

Charter schools were supposed to offer a wider array of options, to help parents find schools based on the educational approach that fits their child best. High test scores were hardly the alpha and omega of the charter idea.

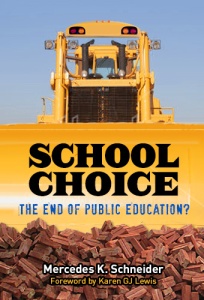

That is true if one goes back to the 1974 conference paper of former Massachusetts university professor, Ray Budde. (Allen does not go this far back.) Budde’s charter idea began with teams of teachers and was indeed pupil-centered. Test scores had nothing to do with Budde’s chartering, which was meant to spur creativity and address student needs within the context of the traditional public school. (I detail this in chapter 5 of my book, School Choice: The End of Publication?.)

Continuing:

But, as Tulane University professor Doug Harris has noted, “when you have intense test-based accountability it really restricts what you can do and to what degree you can innovate because … there are only so many ways to make test scores go up.” …

This is true. Test-centrism stifles creativity. But keep in mind that it is with worship of international test scores that declared “our nation at risk” in 1983– a pivotal moment in declaring American public education a failure and a major leveraging opportunity for the charter concept to morph into the “system-centered reformer” creature from which Allen et al. wish to now separate.

Easier said than done. Ask Victor Frankenstein.

Continuing:

And there’s no telling how many potential charter leaders were either deterred from starting a school or corralled into a cookie-cutter educational approach by policies designed to close charter schools by default for a couple of years of low standardized test scores. Accountability should be about much more than a test. …

Note that the “cookie-cutter” educational approach has also been advanced by the billionaire charter grant funders. More to come on that.

We believe that if offered more freedom, educational entrepreneurs will embrace a variety of different approaches and offer parents a diverse range of options.

This is a nice belief. It lines up with the belief that if I cash in my savings and hand it out to individuals on the street, they will invest it wisely and return it to me with interest out of sheer gratitude and unparalleled integrity.

We accept that more freedom might mean that more schools fail than would in a more regulated environment, but we believe that failure is necessary for success.

I notice that the motto, “failure is necessary for success,” is a fav of ed reformers but that it is rarely accompanied by caveats regarding the destruction that certain failure causes and how not all failure is worth it. School closure disrupts the lives of students, parents, and communities, and too often in regard to charter schools, such closure is abrupt and attributable to fiscal mismanagement and fraud.

Still, all Allen et al. see is the rainbow:

We are optimistic that, over time, the net result of giving educators autonomy and empowering parents to judge schools will drive the creation of a higher quality sector.

As to the earlier statement about charters “supplementing” traditional schools: Now we are “replacing the power structure”:

When conceived, charter schools were supposed to be the antithesis of their traditional public school (TPS) counterparts, unbound from the bureaucratic processes and controls that assure the kind of compliance valued in government schooling. … Charter schools were meant to replace the districts’ exclusive franchise over education with a new power structure. …

Now, what could have happened is a focus on alleviating the bureaucracy for traditional public schools. Instead, corporate ed reform (of which the charter push is certainly a part) has increased the traditional school bureaucratic burden. Just ask any school counselor saddled with testing paperwork, or any administrator burdened with increased teacher eval forms to complete.

Of course, the process can be streamlined, for instance, if those at the top have all of the power and those at the bottom, little to none.

More to come on this corporate-espoused, “top-down” operating of schools.

Note that CER calls its funders “well-intentioned”– but the dig on them is to come. For now, the lament is on how much charter bureaucracy is making charter schools into a replacement bureaucracy for that of the previously-termed “government schooling”:

As the charter movement has grown it has been coopted by well-intentioned advocates, funders, and reform-minded members of the education establishment who have insisted upon systematizing and institutionalizing the sector at both the state and national levels. That institutionalization has come in the form of policy environments and onerous regulations that tightly prescribe the conditions under which charter schools can be established, exist, and grow. As a result, a reform that once promised innovation and true choice for families has come to look more and more like the district school bureaucracies that founders of the charter school movement sought to escape. Rather than differentiated, charter schools and the structures for charter schooling in each state and locality have become similar.

Dare I write that Allen et al. are referring to the current state of charter schooling as having become “status quo”-ish?

I dare.

And now, we return to the origins of the charter school, sort of. Budde is not mentioned, and former United Federation of Teachers (UFT) and former American Federation of Teachers (AFT) president, Al Shanker is, as a promoter of charter schools.

Notice that Allen et al. do not refer to Shanker as a former union president even though he was so twice over, and in the role of AFT president, presented the charter school concept to the National Press Club in 1988 and first used the term “charter” to describe his “school-within-a-school” in the July 10, 1988, New York Times.

The CER excerpt below also does not acknowledge that by December 1996, Shanker was disappointed with the direction charter schools were headed, referring to them as “an oxymoron, a private school that is funded with public money.” (Chapter 5, School Choice: The End of Public Education?.)

But here is what CER writes of Shanker:

As the charter school movement enters its third decade, charter advocates and reform-minded individuals and organizations have a choice to make: will we free up charter schools to once again become a grass roots movement or, as Al Shanker might have had it, a cause that arises from and is driven by each local community—a form of schooling that engages parents and students and empowers teachers and administrators? Or, will charter schools continue to become just another way to “do” public schooling, providing the lucky with an opportunity to attend schools that look alike and produce high test scores but lack the freedom to do anything truly innovative for students? …

Note that Allen et al. assume that charters “produce high test scores.” Now, even as Allen et al. don’t want the focus to be on test scores, the generous default here is that even the bureaucratically-muddled charters deliver on the high-test-score expectation.

And so, that concludes my commentary on the CER book/report excerpt of the introduction. What remains are excerpts from Allen’s long essay, entitled, “Consequences of Scale, Isomorphism and the Charter School Movement.”

What is noteworthy in Allen’s essay is that in taking issue with scaling charters, Allen is taking issue with a principal funder of the charter school push, the Walton Family Foundation (WFF), and, by extension, the billionaire Waltons themselves.

This is a risky move for Allen; offending the Waltons might not fare well for CER, which is funded by the Waltons and by other ed reform scaling billionaires, including the Broad and Gates Foundations.

Even so, the WFF contributions to CER have notably decreased over the past decade (most of the info can be found here, and the rest, here and here):

WFF Grants to CER:

- $100,000 (2016)

- $200,000 (2015)

- $200,000 (2014)

- $541,856 (2013)

- $809,209 (2012)

- $930,662 (2011)

- $518,273 (2010)

- $500,000 (2009)

- $499,450 (2008)

- $550,000 (2007)

Looks like the WFF-CER marriage began to cool c.2014.

If only those Waltons would hand over the funding and just lay off of controlling the charter sector….

Allen opens her essay thus:

Isomorphism, the “constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble the others who face similar environmental conditions,” has taken hold of the charter school sector. Charter schools are independent public schools of choice, accountable for results on a performance contract, and free from most rules and regulations that confine other public schools. When charter schools were conceived more than twenty-five years ago, this freedom was intended to foster innovations in teaching and learning and elicit competitive responses from other public schools.

Now charters are not supplementing or supplanting traditional public schools, just challenging them to be better, kind of like the free market– where the inability to compete means closure. But Allen doesn’t write the “c” word here. Instead, her concern is with the charter school sameness bred of bureaucracy;

However, the charter sector is now influenced by coercive, mimetic, and to a lesser extent, normative isomorphism; Despite seeking to differentiate, its schools and structures have become similar. …

This homogeneity threatens the hallmark of charter schools—performance based accountability with flexibility. If left unchecked, it will result in the demise of the charter sector.

A word about the “hallmark of charter schools”: Allen doesn’t want test scores to be the measure of charter school success. She wants an “open and dynamic system.” She appears to advocate that “flexibility” replace test scores, but just for charters, not for traditional, “government” schooling. And just how “flexible” appears to be left open.

But now Allen takes on the role of the Waltons in driving charter school bureaucracy, and then she criticizes the creation of charter management organizations (CMOs):

Major school reform donors, most notably the Walton Family Foundation (WFF) encouraged charter supporters to organize and coordinate one voice rather than offer competing perspectives on Capitol Hill. The seeds of isomorphism were planted. …

WFF called for a “new national meeting of charter school leaders to discuss how the groups have and might operate better in the future, reflecting on the disagreement that occurred during the federal bill deliberations.” The result was a “coalition” called the Charter School Policy Leadership Council (“the Council”). The Council was intended to “enable and enhance regular, on-going communication among national organizations that support charter schools,” and to strengthen supporters’ “collective ability to effectively and forcefully represent the interests, well-being, and success of the charter movement as a whole …” The Council was to communicate with a single or coordinated voice. Some were concerned: What if there came a time when a particular member or actor might not agree or seek to pursue a particular course? Would new approaches be welcomed as a positive disruption?

Dissension in the ranks was not kindly received. WFF became defensive in the face of alternative opinions about how charters could best be supported nationally. It wanted a “strong, viable, national leadership culture,” and sought to quell group members that questioned the wisdom of such a move. Isomorphism celebrates unity, not diversity.

The Council morphed into a new umbrella organization, now the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools (NAPCS). The Alliance was created to speak for the charter school sector and ensure institutional coordination. It continues to be beholden to the demands of funders and an increasing group of peer organizations who seek to align their demands on state and federal lawmakers into one consistent set of principles and policies, rather than respect the unique character and diversity of laws and policies that made the charter school idea the spark to public education system change from its inception. As the movement for charters became more institutionalized, funders also placed additional pressure on state level intermediary organizations to develop into additional formal state-based networks and associations, ensuring more effective support and advocacy on a state level. Each group had its own ideas about how best to achieve success. Yet national funders remain tied to the idea that these groups be institutionalized.

Parallel to the institutionalization of the charter movement, a new class of nonprofit charter school networks, Charter School Management Organizations (CMOs), arose. CMOs are groups of “replicated” schools run by one centralized group, or organization. Originally referred to as EMOs (Education Management Organizations) and modeled after HMOs (Health Management Organizations), CMOs garnered attention from prominent charter school donors. …

Some believed (and forcefully though not always correctly communicated to funders) that CMOs should replace single charter schools, often referred to as “Mom and Pop” charters. Donors also advocated for CMOs to be not-for-profit, as they felt they would have less influence over for-profit organizations. Eventually, donor support led to the primacy of a not-for-profit tax status in the CMO world. …

Because they are large non-profit organizations, many CMOs exist at the will of funders. This means that funders often influence what schools within these networks look like and how they operate. …

Okay. So, the billionaire funders, many of whom are corporate giants, want to scale charters, and Allen is upset by this. Surely this is not surprising. Know what happens to Mom and Pop General Store when Walmart comes to town? Mom and Pop fold. Period.

The Waltons are not in business to promote small. And they are hardly likely to forego the oversized influence that comes with writing the oversized, charter-funding checks.

But next, Allen takes on Stanford’s charter school study, CREDO. Even as Allen criticizes CREDO for providing faulty research that charter opponents can use as ammo, she neglects the point that anti-charter folk have also criticized CREDO’s methodology (for example, see here and here):

The emergence of large-scale research about charters schools and CMOs has created more pressure for uniformity within the charter movement and inroads to further control the movement from the top-down.

Since the No Child Left Behind era, the federal government has been interested in supporting and expanding successful charter schools, where success is measured as student outcomes on standardized tests. …

On its face, this type of federal involvement seems aligned with the origins of the charter school movement, at least in terms of accountability. But a closer look reveals that one large research study has exercised undue influence over which charters are held accountable and how. Support for additional regulations aimed at closing failing charters stemmed from a flawed 2009 study by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University. The CREDO study claimed only one in five charters perform equal to or better than their public school counterparts. Following the study’s release, lawmakers demanded accountability in exchange for further support of charters and CMOs. Despite criticism from seasoned and respected education researchers, the CREDO study, by virtue of the political influence it wielded, became accepted as fact. …

The political answer to the CREDO study was for policymakers to create more top-down controls for charters. If the charter sector had not become more isomorphic in nature, other voices may have emerged to challenge the data, as well as the notion that state oversight and regulation leads to improved school quality. Instead, the sector silenced members that knew better, giving legitimacy to charter opponents.

Allen wants politicians to turn their backs on the CREDO numbers, and she wants to move away from “top-down” control. But what is particularly intriguing here is that “the sector” appears to be euphemistic for the billionaire charter funders, like the Waltons.

And the Waltons don’t do “Mom and Pop.” But they do buy elections, and they love vouchers (Betsy DeVos’ game of choice, pun intended), so Allen, you’ve got your charter-unsectoring work cut out for you.

Readers, I have only expounded on excerpts from the first 15 pages of the 120-page CER book/report. Allen also criticizes both the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) and the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools (NAPCS) for their roles in institutionalizing/bureaucratizing the charter sector. She further criticizes Netflix founder Reed Hastings’ influence that of New Schools Venture Fund’s John Doerr for favoring CMOs.

A couple additional Allen quotes, in closing:

Like NACSA, NAPCS also forces its vision onto the charter sector by touting standardization and regulation as a means to quality. Each year it ranks state charter school laws, rewarding states that encourage strong oversight roles for authorizers and sophisticated data collection models—a blatant nod to the value that the Association places test scores as an indicator of school quality.

This is one of my favorites:

Risk-averse leaders demand evidence of accountability in exchange for support.

*Give us money and freedom, and we’ll see if responsibility follows.*

What could possibly go wrong?

It’s entertaining to watch the charter sector reckon with its own bureaucratic entanglements– like trying to tap dance off of flypaper.

I’ll leave the rest of the report for readers to peruse.

_____________________________________________________________

Something notable to those in our city who wish to “see” is that where inner-city traditional high schools have been turned into multiple school-sharing charters, the parking lots where previously only a few student cars were parked are now filled to the brim and overflowing with the cars of excessive management personnel….

It’s entertaining to watch the charter sector reckon with its own bureaucratic entanglements– like trying to tap dance off of flypaper.

Jeanne Allen has been caught in the flypaper for a long time.

I think that the charter industry, like public schools, are threatened by the rapid flight to computer-based learning and management systems so-called personalized learning. The vintage foundations got this going but they are not moving as fast as the new kids on the block, including Google Education, the Chan/Zuckerberg Initiative, and Emerson Collective (wealth of Steve Jobs). Check out the website Wrench in the Gears for some excellent reports.

Testing poses a problem leading to standardization of charter schools. Testing, however, is useful in determining the closings of traditional public schools. The depth of analysis in the report is shallow at best. Thanks as always Mercedes.

off topic- A former TFA, “Pete”, has a website, PE+CO, focused on his viewpoint about Louisiana K-12. The site posts info. from the 74, has a DFER patch posted on the home page, etc.

“Charter schools are independent public schools of choice, accountable for results on a performance contract, and free from most rules and regulations that confine other public schools.”

Independent public schools of choice. What a humdinger, eh?

I wonder who holds those schools accountable. The owners??

Hmmm, the reason for those “rules and regulations that confine other public schools” is to actually hold those schools accountable not like the pseudo-accountability of privately owned and managed charter schools.

Ay, ay, effin ay!