Gentrification: Where Affluence Wins.

Gentrification is the process of displacing the original, usually lower-class, residents in an urban area with more affluent residents. It is a controversial means of “improving” the socioeconomics of a city by driving out the previous residents because many original residents can no longer afford to live in the area.

The new, affluent residents are often the ones who enjoy the benefits of gentrification while previous residents, who may already have been hard on their luck, usually become even harder on their luck as they are forced out.

In June 17, 2003, PBS produced a series on gentrification. Writer Benjamin Grant published this informative piece on gentrification related to the film:

Flag Wars tells the story of what happened to the Olde Towne East community in Columbus, Ohio when the neighborhood went through the process of gentrification in the mid-to-late 1990s. For much of the twentieth century, urbanists, policymakers, and activists were preoccupied with inner city decline across the United States, as people with money and options fled cities for the suburbs. But widespread reports of the American city’s demise proved premature. Beginning in the 1970s, urban life slowly began to regain prestige, particularly among artists and the highly educated. By the turn of this century, many cities were thriving again, and their desirability among the wealthy and upwardly mobile was putting intense pressure on rents, real estate prices, and low-income communities.

What is Gentrification?

Gentrification is a general term for the arrival of wealthier people in an existing urban district, a related increase in rents and property values, and changes in the district’s character and culture. The term is often used negatively, suggesting the displacement of poor communities by rich outsiders. But the effects of gentrification are complex and contradictory, and its real impact varies.

Many aspects of the gentrification process are desirable. Who wouldn’t want to see reduced crime, new investment in buildings and infrastructure, and increased economic activity in their neighborhoods? Unfortunately, the benefits of these changes are often enjoyed disproportionately by the new arrivals, while the established residents find themselves economically and socially marginalized.

Gentrification has been the cause of painful conflict in many American cities, often along racial and economic fault lines. Neighborhood change is often viewed as a miscarriage of social justice, in which wealthy, usually white, newcomers are congratulated for “improving” a neighborhood whose poor, minority residents are displaced by skyrocketing rents and economic change.

Although there is not a clear-cut technical definition of gentrification, it is characterized by several changes.

Demographics: An increase in median income, a decline in the proportion of racial minorities, and a reduction in household size, as low-income families are replaced by young singles and couples.

Real Estate Markets: Large increases in rents and home prices, increases in the number of evictions, conversion of rental units to ownership (condos) and new development of luxury housing.

Land Use: A decline in industrial uses, an increase in office or multimedia uses, the development of live-work “lofts” and high-end housing, retail, and restaurants.

Culture and Character: New ideas about what is desirable and attractive, including standards (either informal or legal) for architecture, landscaping, public behavior, noise, and nuisance.

How does it happen?

America’s renewed interest in city life has put a premium on urban neighborhoods, few of which have been built since World War II. If people are flocking to new jobs in a region where housing is scarce, pressure builds on areas once considered undesirable.

Gentrification tends to occur in districts with particular qualities that make them desirable and ripe for change. The convenience, diversity, and vitality of urban neighborhoods are major draws, as is the availability of cheap housing, especially if the buildings are distinctive and appealing. Old houses or industrial buildings often attract people looking for “fixer-uppers” as investment opportunities.

Gentrification works by accretion — gathering momentum like a snowball. Few people are willing to move into an unfamiliar neighborhood across class and racial lines¹. Once a few familiar faces are present, more people are willing to make the move. Word travels that an attractive neighborhood has been “discovered” and the pace of change accelerates rapidly.

Consequences of Gentrification

In certain respects, a neighborhood that is gentrified can become a “victim of its own success.” The upward spiral of desirability and increasing rents and property values often erodes the very qualities that began attracting new people in the first place. When success comes to a neighborhood, it does not always come to its established residents, and the displacement of that community is gentrification’s most troubling effect.

No one is more vulnerable to the effects of gentrification than renters. When prices go up, tenants are pushed out, whether through natural turnover, rent hikes, or evictions. When buildings are sold, buyers often evict the existing tenants to move in themselves, combine several units, or bring in new tenants at a higher rate. When residents own their homes, they are less vulnerable, and may opt to “cash them in” and move elsewhere. Their options may be limited if there is a regional housing shortage, however, and cash does not always compensate for less tangible losses.

The economic effects of gentrification vary widely, but the arrival of new investment, new spending power, and a new tax base usually result in significant increased economic activity. Rehabilitation, housing development, new shops and restaurants, and new, higher-wage jobs are often part of the picture. Previous residents may benefit from some of this development, particularly in the form of service sector and construction jobs, but much of it may be out of reach to all but the well-educated newcomers. Some local economic activity may also be forced out — either by rising rents or shifting sensibilities. Industrial activities that employ local workers may be viewed as a nuisance or environmental hazard by new arrivals. Local shops may lose their leases under pressure from posh boutiques and restaurants.

Physical changes also accompany gentrification. Older buildings are rehabilitated and new construction occurs. Public improvements — to streets, parks, and infrastructure — may accompany government revitalization efforts or occur as new residents organize to demand public services. New arrivals often push hard to improve the district aesthetically, and may codify new standards through design guidelines, historic preservation legislation, and the use of blight and nuisance laws.

The social, economic, and physical impacts of gentrification often result in serious political conflict, exacerbated by differences in race, class, and culture. Earlier residents may feel embattled, ignored, and excluded from their own communities. New arrivals are often mystified by accusations that their efforts to improve local conditions are perceived as hostile or even racist.

Change — in fortunes, in populations, in the physical fabric of communities — is an abiding feature of urban life. But change nearly always involves winners and losers, and low-income people are rarely the winners. The effects of gentrification vary widely with the particular local circumstances. Residents, community development corporations, and city governments across the country are struggling to manage these inevitable changes to create a win-win situation for everyone involved.

Gentrification affects the viability of urban public school systems. One issue is that the new, affluent– younger– residents are having fewer children (or having children later).

Another issue is that even when these new residents have children, they may well choose not to send those children to public schools.

The December 08, 2018, Denverite offers the following information on the impact of gentrification on Denver Public Schools in the article, “Denver’s Student Population Expected to Shrink in 2019 After More Than a Decade of Growth”:

The student population of Denver Public Schools has grown for 13 years straight, but the enrollment boom is coming to an end — a result of gentrification and a significant drop in the birth rate, according to the latest expert analysis.

In 2019, the city’s student population is expected to fall by about 600 students, enough to fill an elementary school. In fact, kids are disappearing already from the gentrifying neighborhoods where young, childless couples are buying up property. …

And you might expect that growth to continue. If the roads and ski slopes are more crowded, why aren’t the schools?

Well, look at who’s moving here. Since 2009, 80 percent of Denver’s transplants have been households without children, according to the latest DPS enrollment report.

Now, eventually, you figure that those people might have kids — but, for many, that won’t happen in the thousands of new luxury apartment units that have hosted so much of the population boom.

“While you may have some people in their upper 20s and 30s that may decide to have kids, I don’t think that the kids are going to be living there,” Eschbacher said.

Also in December 2018 (December 20), the Tennessean published a piece, entitled, “Fewer Students Are Attending Nashville’s Public Schools, Gentrification May Be to Blame”:

Nashville public schools enrollment dropped to 85,287 students in the 2018-19 school year, a decline that a district official said is likely due to the city’s changing neighborhoods. …

Last year, the district had 85,399 students enrolled. In the 2015-16 school year, 86,633 students were enrolled.

Elsewhere, other districts have seen enrollment growth, bucking the trend the city is beginning to see. …

The constant change in Nashville over the last several years has made it difficult to project enrollment, Latimer said.

“Some of it is the cost of housing and some of it is because neighborhoods are gentrifying. You have different families move in,” Latimer said. “If you look at Pearl Cohn (High School), they’ve had more demolitions and more construction than any other cluster. Enrollment has gone down as the housing stock has changed.” …

Last school year, the district budgeted for flat enrollment after last year when the district expected enrollment to grow after years of increases. It also left the district without $7.5 million it expected from the state that would have been doled out for enrollment increases.

Even as the Tennessean was publishing its article on the impact of gentrification in Nashville, Raleigh, North Carolina canceled a city-sponsored talk on gentrification scheduled for Wednesday, December 26, 2018. Apparently the originally scheduled talk did not include the perspectives of locals negatively affected by gentrification:

One of those who complained about this week’s planned talk was Raleigh City Council member Corey Branch. The city can’t be the only voice when talking about gentrification and the displacement of people, he said. Branch represents Southeast Raleigh, one of the areas hit hardest by gentrification.

“No one knew about it,” he said. “There wasn’t proper communication to staff or to council about that topic. Especially since it has such a negative impact on my district.” …

“We have to be very thoughtful,” [council member Nicole Stewart] said. “I think we have to be a convener and let other folks lead so we can learn. So we as a council can learn instead of not listening and not learning. We need to listen and learn.” …

Those local voices, [planning director Ken] Bowers said, need to include people in gentrifying neighborhoods.

For more details on the impact of gentrification on a number of cities, including Boston, Seattle, New York, San Francisco, Washington, DC, Atlanta, and Chicago, see this October 2014 Mic article.

For more on gentrification in New Orleans, see this April 2018 Advocate article.

For the connection between school choice and gentrification, see this March 2018 Atlantic article. Allow me to include a noteworthy bit here:

Pearman and Swain’s national study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Sociology of Education, looked at four different types of school-choice programs: magnet schools, charter schools, private school vouchers, and open enrollment across school districts.

When school choices are limited, poor communities with more white people are the ones more likely to gentrify. When there are more school-choice options, though, it’s the neighborhoods with more people of color that are most likely to gentrify.

The effects were substantial: A predominantly non-white neighborhood’s chance of gentrification more than doubles, jumping from 18 percent to 40 percent when magnet and charter schools are available.

Some takeaways from this post:

- Gentrification displaces original (poorer) residents in favor of the affluent.

- Gentrification favors white people over people of color.

- Gentrification threatens the economic survival of urban public school districts.

- School choice exacerbates gentrification in non-white neighborhoods (which, by extension, threatens the stability of public school systems in the neighborhoods of people of color)

None of that news is good.

Unless, of course, you’re the white, affluent beneficiary.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Interested in scheduling Mercedes Schneider for a speaking engagement? Click here.

.

Want to read about the history of charter schools and vouchers?

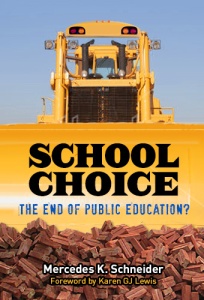

School Choice: The End of Public Education?

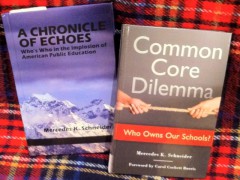

Schneider is a southern Louisiana native, career teacher, trained researcher, and author of two other books: A Chronicle of Echoes: Who’s Who In the Implosion of American Public Education and Common Core Dilemma: Who Owns Our Schools?. You should buy these books. They’re great. No, really.

Don’t care to buy from Amazon? Purchase my books from Powell’s City of Books instead.

Having worked inside Denver’s poorest neighborhoods for many years, it became clear as testing abuses began to invade and blame the teachers, then the schools and then entire neighborhoods, that there was a hidden goal to limit school options for poor kids and push them out, thus allowing gentrification opportunists to then take over and PLAN to ultimately “take back” large schools for future wealthy families. The fact that there may not be enough wealthy family kids to fill the schools is an interesting new twist.

Is that what we call market forces?